Laureate - 2014

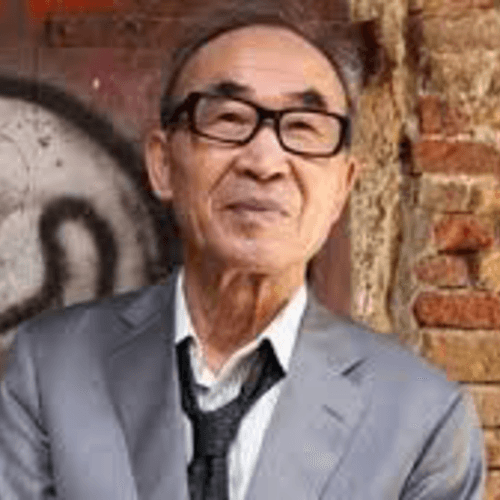

Ko Un

South Korea

Biography

Ko Un was born in 1933, which means that today he is nearer 80 than 70. He is surely Korea’s most prolific writer and he himself cannot say for sure how many books he has published in all. He guesses that it must be about 140, volumes of many different kinds of poetry, epic, narrative, and lyric, as well as novels, plays, essays, and translations from classical Chinese. In the last two decades he has made journeys to many parts of the world, including Australia, Vietnam, the Netherlands, Mexico, Sweden, Venice, Istanbul . . . He makes a deep impression wherever he goes, especially when he is reading his poems in the husky, tense, dramatic manner he favors. It seems to make little or no difference that most of his audience cannot understand a word he is saying. He speaks little or no English but time after time a deep communication is established before anyone reads an English translation or summary of what he had been saying. After the drama of his own performance, the translations usually sound rather flat. Ko Un’s ability to communicate beyond language is a gift that other Korean writers can only envy him for. There are some people who do not seem to need words in order to communicate, it is part of their charisma. There are many barriers to communication and many are the arts by which people have tried to overcome them. In the case of Ko Un, who cannot be every day giving readings, there is an urgent need to make translations of his work available. In bringing Ko Un’s writings to a world audience, I am acting to make cross-cultural communication possible in one particular case. It may be good to begin with a summary of Ko Un’s life story, since that in turn may help to pinpoint some of the difficulties we encounter in translating his writings. He was born in 1933 and grew up in Gunsan, a town on the west coast of North Jeolla Province. Echoes of his childhood experiences in the Korea of the 1930s and 1940s can be found in the earlier volumes of the great 30-volume series known as Maninbo, the final volumes of which were published early in 2010. The traditional life of the farming villages, the intense awareness of extended family relationships, the poverty and the high level of infant mortality all make this a world far removed even from modern Korea, and very unfamiliar to non-Korean readers. Readers are expected to know that when Ko Un was a child, Korea was under Japanese rule, and to know what that signifies for Koreans still today. In 1950, war broke out and Ko Un was caught up in almost unimaginably painful situations, which were in strong contradiction with the warm human community he had grown up in, as Koreans and outside forces slaughtered each other mercilessly. As a child, Ko Un had been something of a prodigy, learning classical Chinese at an early age with great facility, and encountering the world of poetry as a schoolboy through the chance discovery of a book of poems written by a famous leper-poet. His sensitivity was not that of an ordinary 18-year-old and he experienced a deep crisis when confronted with the reality of human wickedness and cruelty. His experiences included the murder of members of his family and the death of his first love as well as days spent carrying corpses to burial. He poured acid into his ears in an attempt to block out the “noise” of this dreadful world, an act that left him permanently deaf in one ear. The traumas of war might have destroyed him completely but he took refuge in a temple and the monk caring for him decided that his only hope of finding a way out of his torment would be by becoming a Buddhist monk, leaving the world at a time when the world was a very ugly place. His great intellectual skills meant that he rapidly became known in Buddhist circles and after the Korean War ended he was given responsibilities. More important to Ko Un were his experience of life on the road as he accompanied his master, the famous monk Hyobong, on endless journeys around the ravaged country. Hyobong had been a judge during the Japanese period and had quit the world to become a monk after being forced to condemn someone to death. Ko Un’s character is intense, uncompromising, he is easily driven to emotional extremes and he soon began to react against what he felt was the excessively formal religiosity of many monks. The reader of his work has sometimes to follow him through shadows cast by intense despair. He felt obliged to stop living as a monk and in the early 1960s he became a teacher in Jeju Island. Later in the decade he moved to Seoul. For several years he lived as a bohemian nihilist while Korea was brought toward its modern industrial development under the increasingly fierce dictatorship of Park Chung-hee. The climax came early in 1970 when Ko Un went up into the hills behind Seoul and drank poison. He nearly died but was found and brought down to hospital. In November 1970 a young textile-worker, Jeon Tae-il, killed himself during a demonstration in support of workers’ rights. Ko Un read about his death in a newspaper he picked up by chance from the floor of a bar where he had spent the night. The impact of such a selfless death changed his life radically. He says that from that moment on he lost all inclination to kill himself. The declaration of the Yushin reforms in 1972, by which Park Chung-hee became president for life and abolished democratic institutions, sparked strong protests among writers and intellectuals as well as among the students who have always acted as Korea’s conscience. In the years of demonstrations and protests that followed, Ko Un’s voice rang out and he became the recognized spokesman of the ‘dissident’ artists and writers opposed to the Park regime. He was often arrested and is today hard of hearing from beatings he received then. When Chun Doo-hwan rose to power in 1980, Ko Un was arrested along with Kim Dae-jung and many hundreds of Korea’s ‘dissidents’ and he was sentenced to 20 years in prison. It was there, as he faced the possibility of arbitrary execution, that he formed the project of writing poems in commemoration or celebration of every person he had ever encountered. No one, he reckoned, should ever be simply forgotten, since every life has immense value and is equally precious as historical record. This was the origin of the poems in the Maninbo (Ten Thousand Lives) series. Once the new regime felt sure of its hold on power, most of the prisoners were amnestied. Ko Un was freed in August 1982, in May 1983 he married Lee Sang-Wha, and in 1985 a daughter was born. He went to live in Anseong, two hours from Seoul, and began a new life as a householder, husband, and father, while continuing to play a leading role in the struggle for democracy and for a socially committed literature. There are people who say that a poet’s life has nothing to do with the poems he or she writes but that is hardly tenable. It is a theory that considers poetry uniquely from a formal standpoint and excludes every aspect of personal, social, or historical context. Yet every word Ko Un writes is rooted in and informed by the experience of life I have just outlined. It is inconceivable that a man with such a life-story should not write poems deeply marked by it. He has a very intense sense of history, and of his writing as a mirror of Korean history. Books of Poems Other World Sensibility(1960), Seaside Poems(1966), God, the Last Village of Language(1967), Senoya, Senoya: Little Songs(1970), On the Way to Munui Village(1977), Going into Mountain Seclusion(1977), Early Morning Road(1978), Homeland Stars(1984), Pastoral Poems(1986), Fly High, Poems!(1986), The Person Who Should Leave(1986), Your Eyes(1988), My Evening(1988), The Grand March of That Day(1988), Morning Dew(1990), For Tears(1991), One Thousand Years’ Cry and Love: Lyrical Poems of Paektu Mountain(1990), Sea Diamond Mountain(1991), What?—Zen Poems(1991), Songs on the Street(1991), Song of Tomorrow(1992) The Road Not Yet Taken(1993), Songs for ChaRyong(1997), Dokdo Island(1995), Ten Thousand Lives, 20 Volumes(1986-1997), Paektu Mountain: An Epic, 7 Volumes(1987-94), A Memorial Stone (1997), Whispering(1998), Far, Far Journey(1999), South and North(2000), The Himalayas(2000), Flowers of a Moment(2001). Poems Left Behind (2002). Novels Cherry Tree in Other World(1961), Eclipse(1974), A Little Traveler(1974), Night Tavern: A Collection of Short Stories(1977), A Shattered Name (1977), The Wandering Souls: Hansan and Seupduk (1978), A Certain Boy: A Collection of Short Stories(1984), The Garland Sutra (Little Pilgrim)(1991), Their Field(1992) The Desert I Made(1992), Chongsun Arirang(1995), The Wandering Poet Kim, 3 volumes(1995), Zen: A Novel, 2 Volumes(1995), Sumi Mountain, 2 volumes(1999) Collections of Essays Born to be Sad(1967), Sunset on the G-String(1968), Things that Make Us Sad(1968), Where and What Shall We Meet Again?—A Message of Despair(1969), An Era is Passing(1971), 1950s(1973), For Disillusionment(1976), Intellectuals in Korea(1976), The Sunset on the Ghandis(1976), A Path Secular(1977), With History, With Sorrow(1977), For Love(1978), For Truth(1978), For the Poor(1978), Penance to the Horizon(1979), My Unnamable Spiritual(1979), Flowers from Suffering(1986), Flow, Water(1987), Ko Un’s Correspondence(1989), The Leaves Become Blue Mountain(1989), Wandering and Running at Full Speed(1989), History is Dreaming(1990), How I Wandered from Field to Field(1991), The Diamond Sutra I Experience(1993), Meditation in the Wilderness(1993), Truth-Seeker(1993), I Will Not Be Awakened(1993), At the Living Plaza(1997), Morning with Poetry(1999) Travel Books Old Temples: My Pilgrimage, My Country(1974), Cheju Island(1975), A Trip to India(1993), Mountains and Rivers, My Mountains and Rivers(1999), Works of Literary Criticism Literature and People(1986), Poetry and Reality(1986), Twilight and Avant-Garde(1990), Biography A Critical Biography of Yi Jooung-Sup(1973), A Critical Biography of the Poet Yi Sang(1973), A Critical Biography of Han Yong-Un(1975) Autobiography Son of Yellow Soil: My Childhood(1986), I, Ko Un, 3 Volumes (1993) Translations Selected Poems of the Tang Dynasty(1974), Selected Poems of Tufu(1974), Chosa: Selected Poems by Kulwon(1975) Editions Several works of old Korean poetry and songs. To say nothing of some Children’s Books Awards Korean Literature Prize(1974) Korean Literature Prize(1987) Manhae Prize in Literature(1989) Joong-Ang Prize for Literature(1991) Daesan Prize for Literature(1994) Honorary resident of Jeong Seon County, KangWon Province (1997) Manhae Grand Prize(1998) Buddhist Literature Prize(1999) The Republic of Korea’s Silver Order of Merit in Culture (2002) Danjae Prize(2004) Unification Award(2005) Bjornson Order for Literature, the only Norwegian Order for Literary Merits(2005) Swedish Literary Prize ‘the Cikada Prize” (2006) Young-Rang Poetry Award(2007) Yusim(Mind) Literature Prize(2008) Lifetime Achievement Prize (Griffin Fund for Excellence in Poetry, Canada, 2008) Korea Academy of Arts Award(2008) Honorary doctoral degree from Dankook University (2010) Winner of The America Awards for a Lifetime Contribution to International Writinlng (2011) Honorary doctoral degree from Jonbuk University (2011) Honorary resident of Jeju Special Autonomic Province (2011) Membership of Honor Committee of World Poetry Academy (2011) Honorary citizenship of Gwangju Metropolitan City (2012) Honored to be a Human Evergreen Tree (2012) Honorary Fellow from Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy (2013)